Overview

Sink down mountain, raise up valley… is a tune from the 1830s folk song regionally linked to Talabot, one of the Saint Simonian monks, an encounter to come. Heaviness of an old fabric – a recycled curtain is at the threshold of this, at times vague, at times historically precise journey. Where once said, sung, drawn or invented things, various objects and motives, come in the way, form found and created imagery, causing distant or rather recent periods to resurface thus creating a vocabulary which is deliberately incomplete and at times hidden in meaning. Unknown or repeating itself, it gives as much or as little away as to always keep it a secret in the society that surrounds it.

At the centre of Ulla von Brandenburg’s exhibition Sink Down Mountain, Raise Up Valley is an episode from a retreat of the commune of Saint-Simonians – a French political and social movement of the first half of the 19thcentury. An age that stands for a transitory period, just before the modern times, when people still believed things they couldn’t see or things that didn’t last, it speaks for a certain romantic angst decades before the distinctive and invading fin de siècleatmosphere. Inspired by the ideas of a utopian socialist, the founder of sociology and a prescient “madman” – Claude Henri de Rouvroy, it follows the Saint-Simonian ideology of a future society based on the spirit of science and industry, where each individual would find fulfilment through the exercise of his or her productive powers in a hierarchical society that is overseen by technocrats.

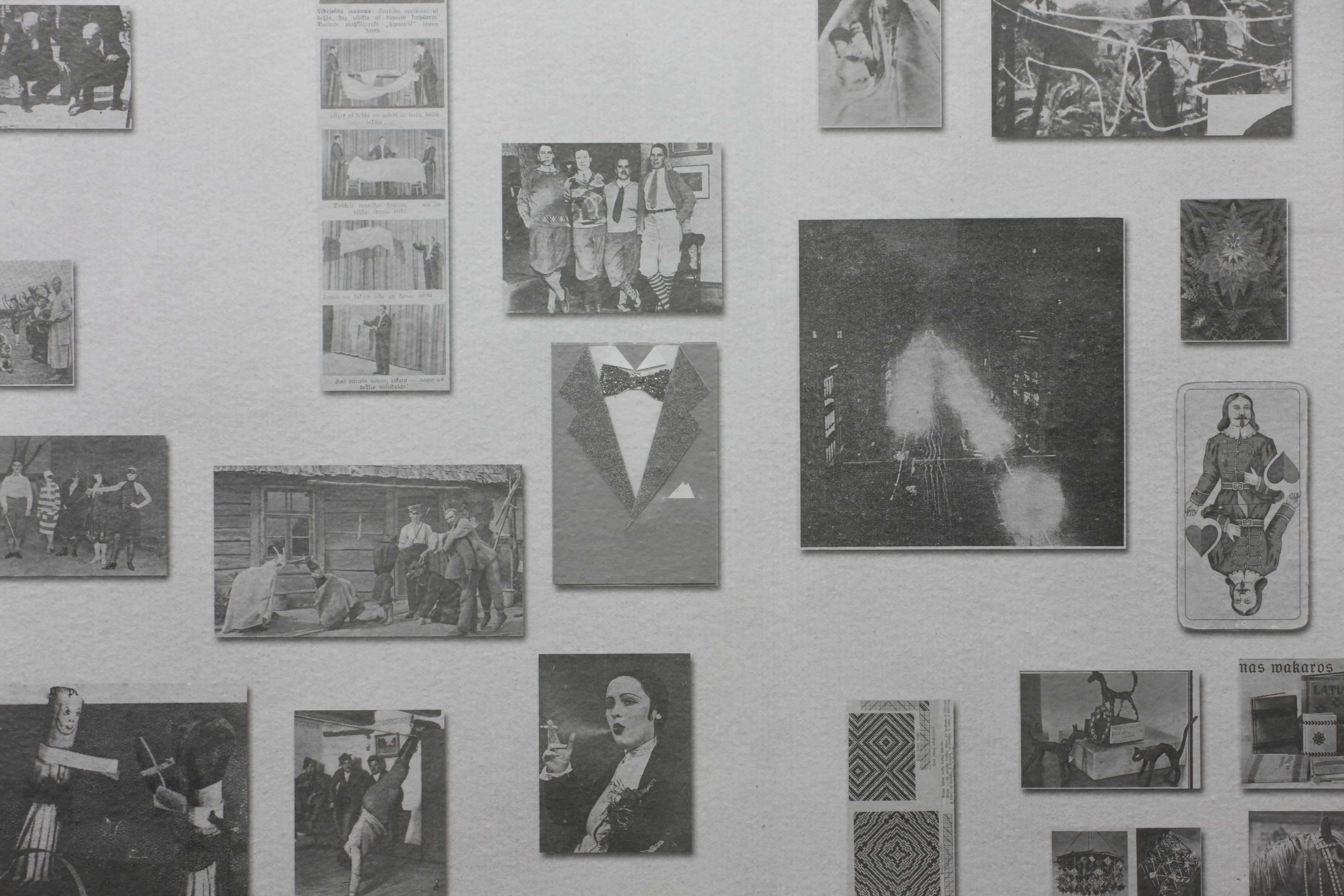

The exhibition unfolds as an initiation via pieces such as the take away journal of 1920s lifestyle imagery (e.g. Atpūta magazine) accompanied by the artist’s own documentation of various ephemera, a pile of uniformly branded tobacco boxes, the downhill construction of a painted and slightly worn-out wooden stage precisely repeating the margins of the tiled gallery’s floor; the attractively shaped and colored objects-props of an eye, a box with ribbons, stairs, a compass and others, and discretely folded costumes of the departed or absent bodies of the characters – all for a better understanding of the final act.

In a black and white single continuous take, a film-performance holds scenes of highly stylized ensembles with watering plants, choreographed gestures, dressing, and singing that references the Saint-Simonians and now simultaneously belongs to the actors of The New Riga Theatre that inhabit it. They walk through the theatre building on a path of a tableaux vivant of static extras, towards the stage for yet another celebration of the singing tradition – so common for Saint-Simonians as well as Latvians. The film characters lip-sync to themselves as for an offstage choir, providing an irritatingly alienated presence that contributes to the overall air of mystery that speaks to the many selves.

As somewhat fictional characters, Saint-Simonians longed for a woman “wiser than man” messiah to come to educate and to liberate them. She is there in the film’s final chords, penciled-in by von Brandenburg to revisit and as a gesture for a lost and at times lessened call for an emancipation of every kind. The installation, poetic and dream-like, but not completely divorced from reality alludes to the uncertainties and anxieties of our time. It functions as a theatrical void waiting/wanting to be completed by the viewer – a key for every set.

Ulla von Brandenburg’s work is characterised by the diversity in the media she uses, which in turn translates into a thematic concentration. Certain motifs appear in different contexts, performances reger back to ideas in wall paintings, drawings prove themselves to be preliminary studies for films, and the props in films become objects in their own right. Her idea of carnival as a legitimate transgression of social order meets with the notion of mask as a desire for new identity and the confusion of reality and appearance in theatrical stagings.