Overview

Pilar Corrias is pleased to announce a solo exhibition of Shahzia Sikander at the Eastcastle Street gallery. The exhibition will include painting, drawing, animation and mosaic, showcasing the breadth of the artist’s multi-valent practice. Sikander is renowned for recasting pre-modern Central and South Asian manuscript practices into avant-garde ruptures, deconstructing archetypal narratives around femininity, race, memory and migration.

On Shahzia Sikander’s ‘World-Forming’, Dorothy Price

"The fact that the world is destroying itself is not a hypothesis: it is in a sense the fact from which any thinking of the world follows." (1) Jean-Luc Nancy (2002)

French philosopher, Jean Luc Nancy’s contention, in the epigraph cited above, that we are in an era of global destruction precipitated by the disasters of colonialism as implemented by the economic imperatives of the West, is one that he attempts to think through in his beguiling philosophical study, The Creation of the World or Globalization (first published in France in 2002). For Nancy, the devastating impacts of neo-liberal globalisation on the social fabric of planetary existence are conceived as a death drive from which alternatives must be sought if we are not to be eviscerated by the ‘un-world’ left in its wake.(2) Nancy’s text becomes one way of thinking through the possibilities of mondialisation or ‘world-forming’ that he posits as distinct from the disregard for humanity, difference and the individual, inherent in the universalising economic impulses and market-driven values of the global. Nancy’s concept of mondialisation is understood as an approach to ‘being-in-the-world’ in which an inexhaustible struggle for justice must reside.(3) Whilst his text remains philosophically abstract but enticingly suggestive, Shahzia Sikander’s poetic and multivalent art practice might be viewed as visually materialising similar or parallel concerns. Yet in Sikander’s ‘world-forming’ it is the role of the feminine in the constructive possibilities of a new world order that is brought to the fore.

Infinite Woman

Women in Sikander’s practice are agents of resistance, change, nurture and power. They are centred as symbols of endurance and transformation within vast global histories of Empire to local inflections of colonial dominance and ecological disaster; and they become both literal and metaphorical ‘touchstones.’ Infinite Woman (2021), the eponymous work from which the exhibition at Pilar Corrias takes its name, is a perfect example of the centrality of the female form to Sikander’s planetary imagination, which literally radiates and revolves around women’s bodies. The multi-coloured, identically-shaped female forms (and their shadows) become the radial axes that both emanate from and dissolve into the edges of an intricately painted sphere, encrusted in small patches of ochre, blue, green and black – is it a sun or the scorched earth? Perhaps both. Whilst the work is static, the repetition of forms in circular motion evokes the dizzying, rhythmic disjunctions of Sikander’s mesmerising animations. Indeed, even a short video like Reckoning (just over four minutes, comprised of hundreds of digitally layered, scanned drawings), engenders from the outset the destabilising effects of the sublime. One feels giddy and light-headed in the palpably visceral experience of this work, a film that expands the limits of the fathomable. As curator Hou Hanru has observed, ‘whether on a small piece of paper or an immense video screen’ Sikander’s artworks ‘are like scenes of genesis. A whole world, with everything, every life we can imagine, is given birth from a tiny nucleus...a drop of ink at the center...spinning, radiating.’ (4)

From Reckoning to Touchstone

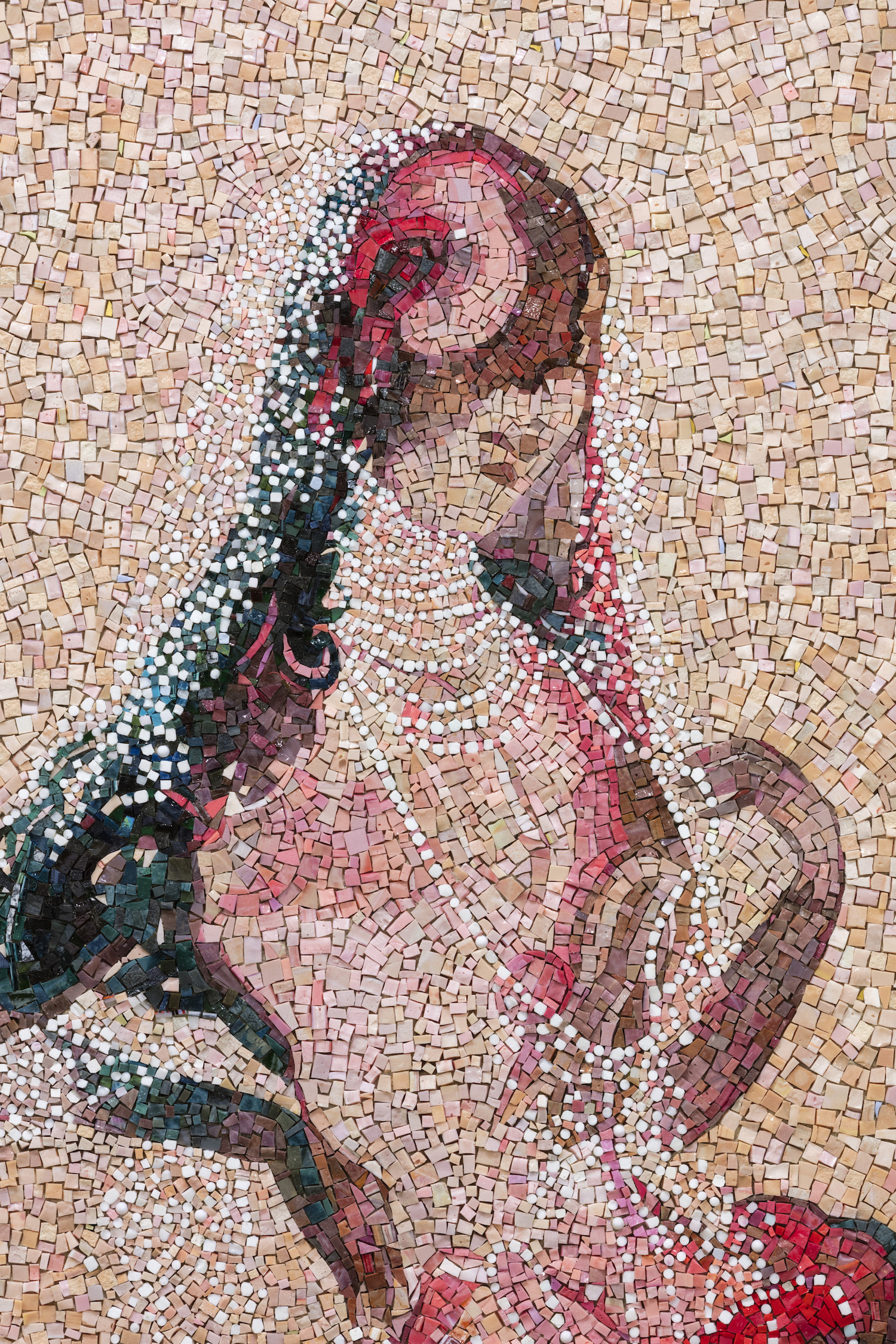

In Reckoning, Sikander’s ‘world-forming’ begins with a visual swarm of small gold shapes against a black ground, from which emerge two floating figures locked in conflict - the empowered and the oppressed, perhaps symbols of Empire and resistance and the myriad consequences wrought by the inhumane destruction of bodies and land through centuries of plantation slavery, indentured labour and enforced migration. The figures are engaged in a reckoning of sins before they dissolve behind a pool of water in which the tendrils of branches encircle one another in a rhythmic dance that generates verdant blossoms. The dried branches are shadowed by the fertile blooms before all the elements succumb once again to the void. In the unfolding of one short 4 minute and 16 second sequence, themes of creation, conflict, tension, colonialism, ecology, fertility, dark matter and void across time and space are held in tension. The viewer is never allowed to rest over one or another, but of necessity holds them all in the cyclical rhythm of Sikander’s expansive and mobile vision. Indeed, the blossoms, branches and tendrils that dance together at the end of Reckoning resurface in Sikander’s mesmerising mosaic Touchstone (2021) in which an Indian woman holds a chalawa (a kind of ghost or spirit in Punjabi) a figure who escapes her grasp and can’t be contained. The woman herself reprise Sikander’s longstanding interest in disrupting traditions of Indian manuscript painting. In Touchstone, she upends the normally miniature scale, transforms the materials from ink to glass and deconstructs the sequential narrative potential. As with much of her work, it is the woman who embodies the Touchstone of the title, both literally in the tactile physical properties of the mosaic tiles and metaphorically in the centrality of the feminine to Sikander’s visual thinking across her chosen media. Indeed, indeterminate possibilities and richly associative visual language are central to a vocabulary that allows her to explore a vast array of iconographic symbolism. The redemptive possibilities of women’s bodies set against the extractive logic of global capital, as suggested in both Infinite Woman and Touchstone are also evident in works such as Kindred, Emanate, Land of Tears and Gold and Diamond (all 2021) in particular.

‘Always winter and never Christmas; think of that!’ (5)

Rendered in various shades of rich lapis blue, Land of Tears is one of a series of works of so- called ‘Christmas Trees’, oil rigs that have come to symbolise the tragedy of capitalism premised on the instrumentalised extraction of the earth’s natural resources to the point of depletion and planetary destruction. As Sikander notes, the motif is based on a photograph of an oil pumping platform that she found in a 1962 BP (British Petroleum) magazine in which she discovered that the rigs were known colloquially as ‘Christmas Trees’ due to their conical shape, piped ‘branches’ and chain ‘garlands’. The irony of the name stuck; a ghoulish dialectic between the gift-bearing properties of the trees that, as Ayad Akhtar notes, ‘promised abundance while being engines of extraction, exploitation and planetary violence. Like a terrible, ineluctable seductive god.’ (6) Or inversely reminiscent perhaps, of the faun’s lament from The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe in which the inhabitants of Narnia are cursed to live in a permanent state of Winter, ‘but never Christmas’. In Narnia, it is the endeavours of Lucy, the youngest ‘Daughter of Eve’ as described in the novel, who provides the redemptive possibilities for the curse to be broken. In Land of Tears, the ‘gifts’ beneath the tree are two female forms, one living, one skeleton, holding on to one another for affirmation and support, as though summoning the strength of ancestors. And it is these women and others on whom Shahzia Sikander’s expansive and versatile practice of seeing-differently, of ‘world-forming’ for future hope against the environmental catastrophe of the Anthropocene, pivots.

1 | Jean-Luc Nancy The Creation of the World or Globalization (first published in French in 2002; New York, Suny Series in Contemporary French Thought, 2007), 35.

2 | Jean-Luc Nancy The Creation of the World, 2002, 34.

3 | The term ‘being-in-the-world’ is one that Nancy borrows from Heidegger’s concept of Dasein, outlined in Martin Heidegger Being and Time (Sein und Zeit) (Tübingen, Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1927).

4 | Hou Hanru ‘Beyond What Words Can Tell. On Shahzia Sikander’s work’ in Hou Hanru and Anne Palpoli (eds.) Shahzia Sikander. Ecstasy as Sublime Heart as Vector (Italy, MAXXI, 2016) 51.

5 | C.S. Lewis, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, London (1950), 23.

6 | Ayad Akhtar and Shahzia Sikander ‘The Incantatory Power of Ayad Akhtar and Shahzia Sikander’ The Nation, 15 September 2020 available https://www.thenation.com/article/culture/sikander-ayad-akhtar- interview/