Overview

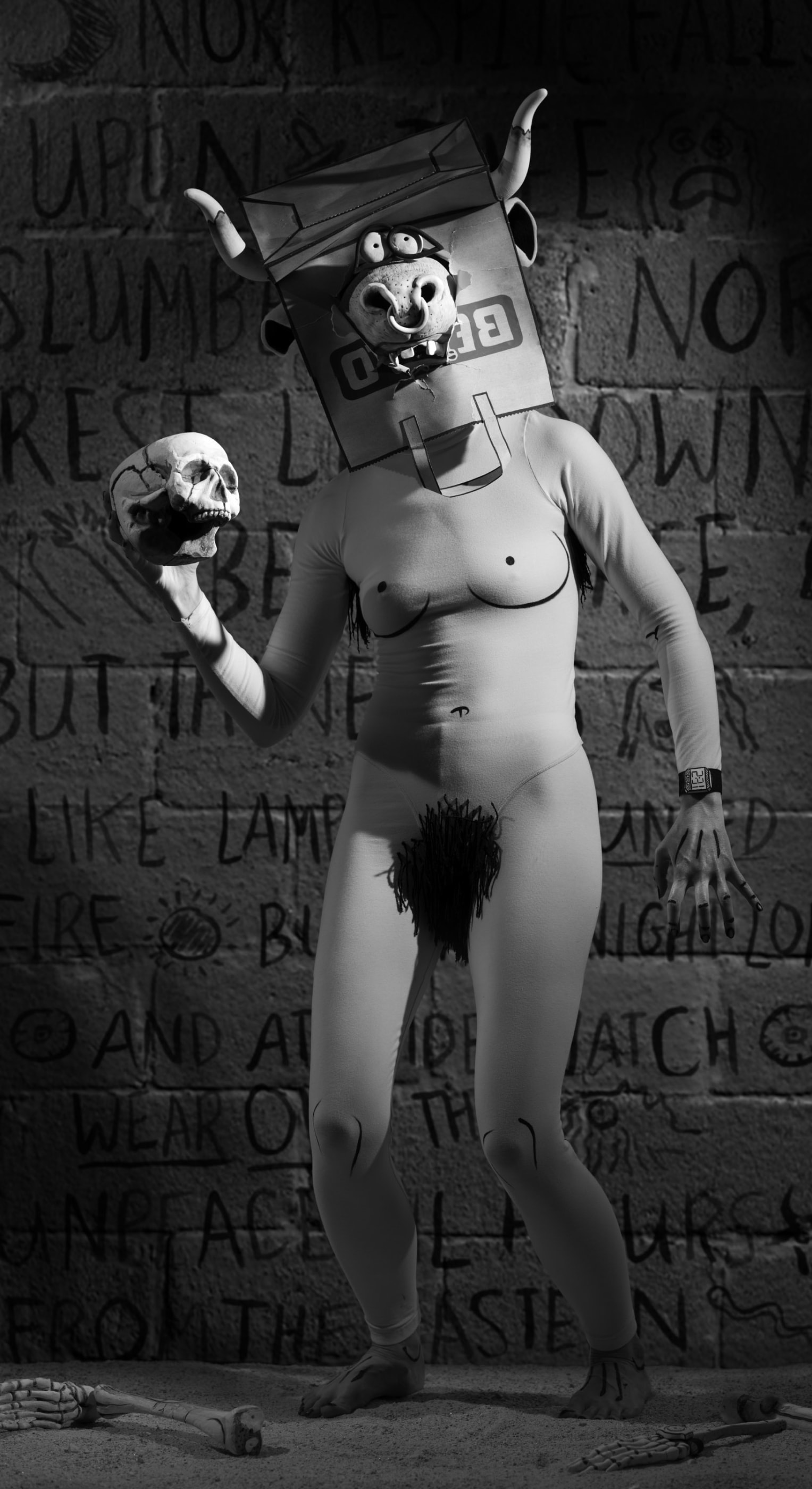

The US artist Mary Reid Kelley is presenting a video from 2011, The Syphilis of Sisyphus, as well as her film This is Offal (2016), which enters the Mudam's collection. Reid Kelley, a trained painter, who since 2008 has made eight films – from the script, props and costumes to filming and editing – in collaboration with Patrick Kelley, realised very early on that she could not express all she wanted to with painting alone. Her black-and-white films are artistic syntheses that combine moving pictures with highly allusive, humorous poetry within an aesthetic that seems almost expressionistic. The focus is always on serious and tragic figures in pointedly artificial narratives; so far, the artist has engaged with themes related to World War I, the 19th century and ancient Greek mythology. But Reid Kelley's films are far from being realistic descriptions. On the contrary, the artificial, grotesque style of the language and images creates an alienation effect in which elements of Greek tragedy, with its accompanying chorus, and of Bertolt Brecht's epic theatre combine to create an extremely intense artistic fusion capable of giving adequate expression to the topic in question. The point of view throughout is a feminist one, with the question of women's role in society a recurrent theme in all her works up to now.

In The Syphilis of Sisyphus, Reid Kelley uses the example of a prostitute in mid-19th-century Paris to spotlight the age-old conflict of women between reality and appearance. In its allusion to the famous text by Albert Camus, the name of the main character, Sisyphus, suggests the absurdity of her existence and implies that for this young woman, defiance and conformation is the only possible attitude. As a former revolutionary, she was once a believer in devotion to nature à la Rousseau. But in the face of necessity, she pragmatically decided against the irrationality of revolutionary upheaval, turning away from naturalness towards artificiality, as advocated in Charles Baudelaire's ‘In Praise of Cosmetics’, the apologist of modern life, to whom there are countless allusions here. As a ‘fallen’ beauty in the Paris of 1852, the year in which, for Karl Marx, history repeated itself as a farce with the proclamation as emperor of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, Sisyphus saw herself quickly locked up, for having all too loose morals, in the madhouse of the Salpêtrière, where Jean-Martin Charcot was later to produce a famous example of a very male point of view with his research into hysteria. The theatrical character of the work is underlined by the Saltimbanques who mark out the absurdities of the temporal framework in a mixture of Greek chorus and French vaudeville. In addition, Reid Kelley uses anapaestic tetrameter for her text, a metrical pattern that was typically used in the Greek classical period for introductions to odes and in modern times for comic limericks. This artful interweaving of pictorial and textual references, this huge wealth of historical and cultural allusions, combined with the exploitation of the possibilities of video technology, fully exemplifies the special charm and depth of Reid Kelley's works.

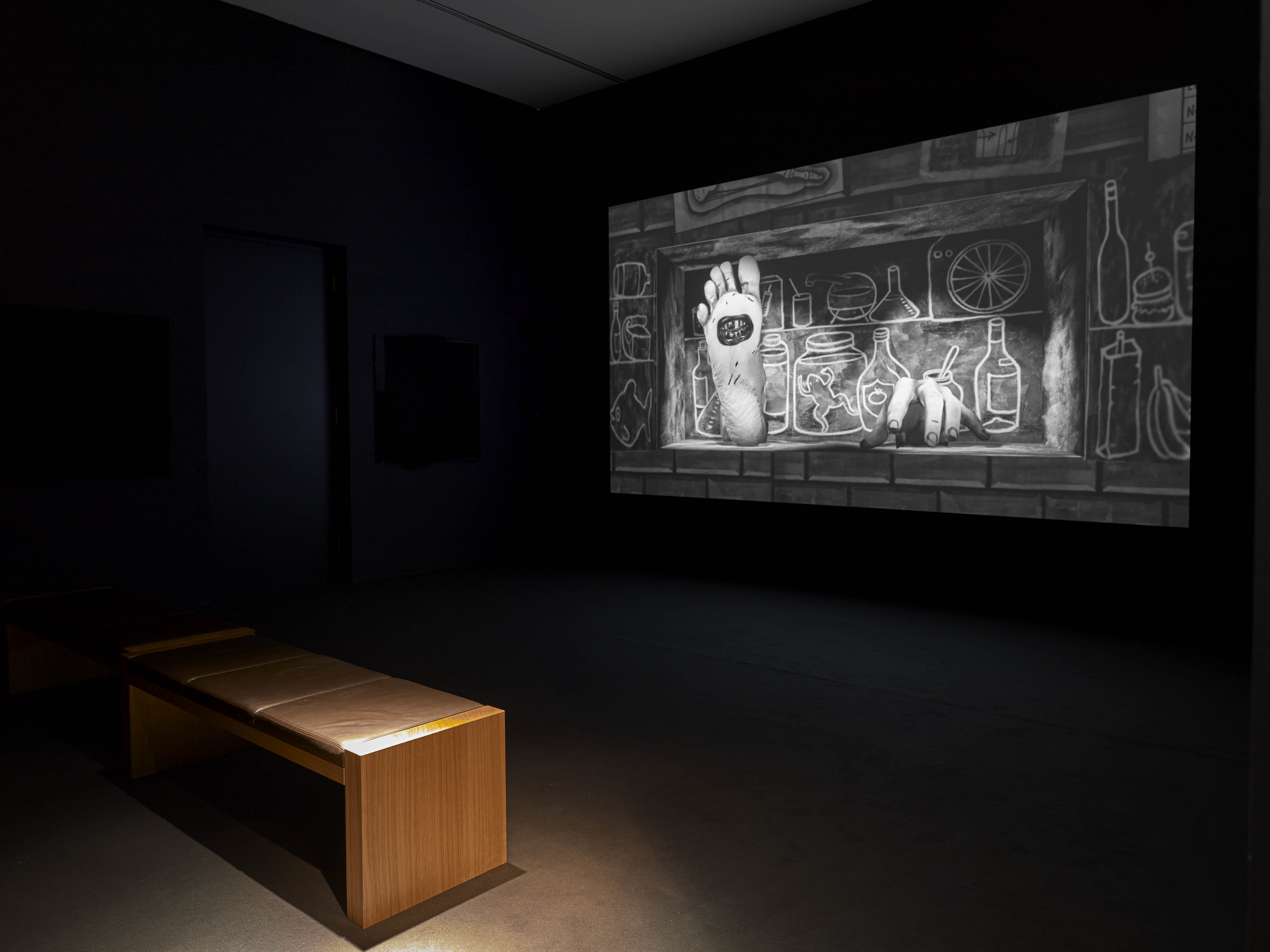

In This is Offal, Reid Kelley also follows these principles. The artist touches here on a serious theme – a young woman's suicide – in a playful manner. She presents an intriguing quarrel between the organs and body parts of the dead woman, which all have different opinions about the reasons for her act and the consequences of it, and give one another the blame. While the heart naively hopes to live on through transplantation, the brain is confronted by vehement reproaches from the liver, which considers it to be behind the unhappy incident. The body itself is pleased to be able to aid science, while the forensic medical expert examining the corpse begins to have misgivings about his job in the face of such senselessness. In this film, Reid Kelly caricatures certain literary clichés, such as that in the famous poem The Bridge of Sighs of 1844 by Thomas Hood about the suicide of a ‘fallen’ young woman who jumps from a London bridge out of despair and poverty. At the same time, she is making an ironic commentary on the saying by Edgar Allan Poe from 1846, for whom ‘the death [...] of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.’ For Reid Kelley, her protagonist is ‘the opposite of Poe's ideal’. As opposed also to Albert Camus's idea of revolt as a response to the absurdity of life, the dead young woman perhaps yielded to the temptation of suicide without being completely aware of the finality of her act. This finality is stressed by the artist with an allusion-rich wordplay at the end of the film, when it becomes clear that the river isn't just any river, but that of the Underworld: ‘This is the river that the boatman picks, you can't be pulled from it, because it Styx.’

Views of the exhibition Mary Reid Kelley, Mudam Luxembourg, 2017 © Rémi Villaggi / Mudam Luxembourg