Overview

Within the context of traditional Western (Colonial) art history, the relationship between the femme bodied sitter and the artist is one predicated on a hierarchical binary interaction: voyeur and object of desire; maker and object; author and subject. This dynamic is particularly acute when the subjects are survivors of Colonial imposition. Take the Colonial Masters (pun intended) such as Gauguin or Picasso, who all but erased the agency, vibrancy, autonomy of their subjects. One could argue that this type of portrait painting, steeped in a colonist mindset, is/was a violence.

Within the context of traditional Western (Colonial) art history, the relationship between the femme bodied sitter and the artist is one predicated on a hierarchical binary interaction: voyeur and object of desire; maker and object; author and subject. This dynamic is particularly acute when the subjects are survivors of Colonial imposition. Take the Colonial Masters (pun intended) such as Gauguin or Picasso, who all but erased the agency, vibrancy, autonomy of their subjects. One could argue that this type of portrait painting, steeped in a colonist mindset, is/was a violence.

It is rare to think of the relationship between master artist and his subject as one of open dialogue, agency, or collaboration - until now. Enter: Gisela McDaniel, a young femme artist whose bold yet tender paintings explode the expectations of art history. Her multidisciplinary practice, notably the large-scale mixed media portraits of womxn and femmes of the Global Majority, is oriented around creating a dual sense of safety and empowerment, not only for the audience but primarily for her subjects.

She works with her sitters (a term used in lieu of ‘subject-collaborator’ indicating an active engagement with the artist) to articulate dynamic visibility beyond the bodily form. At its core, McDaniel’s figurative paintings have always been anti-Colonial. A femme painting other femmes and non-binary folks of the Global Majority is in and of itself a radical act. But even beyond that McDaniel takes an active approach in disrupting the White Supremacist, Capitalist, Patriarchal foundations of Western painting by deliberately amplifying people who have existed on the periphery of Western interest. This act is a means of creating visibility for the historically erased and a simultaneous opposition to the continued encroachment of contemporary Colonialism throughout the world.

McDaniel’s newest body of work and the focus of her solo exhibition, Manhaga Fu’una (Fu’una’s Daughters), is her most deliberate move in this direction. This series of paintings and accompanying soundscapes are specifically focused on diasporic Famaloa’an CHamoru (Chamorro women), the indigenous community from the Marianas Islands in the north-western Pacific. Her initial interest in this specific region comes from her personal heritage; she is a person of CHamoru descent from the island of Guåhan (Guam). In addition to her own relationship to Guåhan, McDaniel is broadly invested in the obliteration of Colonial whitewashing, and as an American territory, Guåhan is the poster child for the realities of Western imperialism and erasure.

The language, mythologies, histories, and dance – according to one of McDaniel’s sitters – are all but diluted or destroyed. In Manhaga Fu’una, McDaniel tirelessly combats this, not through broad strokes envisioning of histories, but through intimate portraits and individual narratives of CHamoru descendants who keep cultural torch aflame.

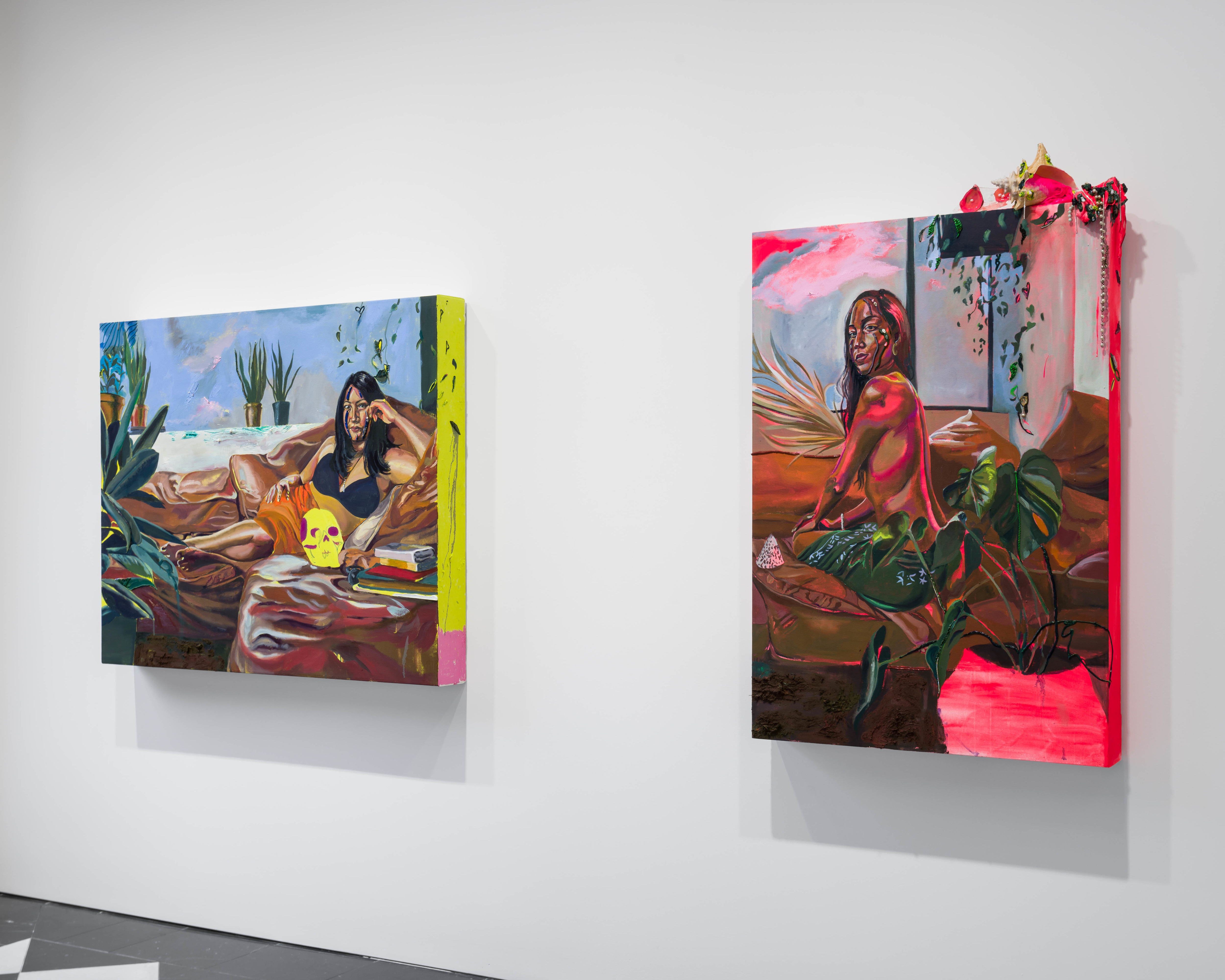

Hung in community with one another, McDaniel’s rich and lovingly rendered paintings centre sitters who have often been dismissed or ignored in hegemonic Western society. With each painting, the artist strives to undo the pervasive and perpetual act of invisibilising CHamoru and diasporic voices. Each sitter gazes with a pointed and self-affirming unabashedness back at the viewer. Måmes (2021), for example, features Dan Taulapapa McMullin, a Samoan-Polynesian indigenous post-colonial Oceania fa'afafinea queer, multi-disciplinary artist, who stares with a casual disregard at the viewer. Adorned in a vibrant lima bean green pāreu with chin in hand, Dan relaxes on a verdant grassy hillock as though to say, ‘I am here. Impress me.’ It is worth noting how McDaniel depicts the environment around her sitter. The painting is a cacophony of glowing lime and moss greens, stippled and stroked across the picture plain; a midground punctuated by deep forest greens squirted from the tube; cotton puff flora erupting from spindly twigs; deliberately placed spiked buds firecracker across Dan’s wrapped lap and knees. Like all of McDaniel’s paintings, the lush surrounding is more than a backdrop. It is a nod to the South Pacific islands - a reinforcement of the subject's story.

McDaniel’s aim is to create an arena of reclamation for her sitters: a space in which they may share intimate parts of themselves on their own terms. As part of her process, she cultivates a relationship with each sitter as a ritual of creating safety, compassion, and catharsis. The outcome of this process is a bond akin to siblinghood: an intersectional and complex essence that is multidimensionally coded within the expansive tableau. McDaniel respectfully refers to the sitters depicted in Manhaga Fu’una as “Mañe’lu” (a non-binary term for “siblings”) “Primas,” or “Aunties.”

One of the ways in which the artist connects with her subjects, both familiar and newly acquainted, is through an exchange of small yet meaningful objects that ultimately become part of each composition. McDaniel incorporates these physical elements in a myriad of ways. In some paintings, these items are used functionally (necklaces are wrapped around the figure's neck, or earrings adorn their ears). In other moments, small materials are used to enhance the texture of the surroundings; in CHelon Tiha (2021), teeth, rhinestones, gold earrings, and barrettes melt into the paint-squeezed foliage. In Inagofli’e (2021), baubles and a conch shell are used as ornamentation along the canvas edge. Often, brikabrak (loose shells, glass and plastic beads, or paint worms) embellish the visage of the figure.

These assorted objects hold emotional significance and power for each of McDaniel’s subjects. The function or significance of these delicate pieces are not disclosed to the viewer, nor is their meaning always disclosed to the artist. The purpose of these items is to reaffirm and buttress something for the sitter who featured in the painting - a faithful secret power.

McDaniel creates pictures that holistically demonstrate the depth and nuance of each person in a manner that transcends language. Accompanying each work is an edited audio portrait that serves as a multi-sensorial supplement to the static works, emphasising the underlying idea that the subjects are portrayed on their own terms. Furthermore, the multisensory approach to portraiture is a way of conveying multidimensionality of the subject. One of the primary issues with Eurocentric/Euro-originated portraits is the flattening of the subject. Voyeur paintings are reductive. They are erotic and exotic without dynamism. McDaniel combats this tradition by incorporating a plethora of entry points into her sitters’ narrative. Her purpose is not only to expatiate each individual story, but to reinvigorate the sparks of colonised cultures that are rapidly being deoxygenated.

By Jasmine Wahi, Co Director, Project for Empty Space.