Overview

Pilar Corrias hosts a solo exhibition by Mary Ramsden featuring a series of new paintings.

Coversation between Mary Ramsden

and writer & curator Isobel Harbison

Isobel Harbison: Your paintings often have exposed under layers visible in the corners, margins or frames, indicating the painterly processes and various tempos within the work. Since your show 'Swipe' in 2015, that sense of time was juxtaposed with an immediacy of smart phone usage. What does the ubiquity of "smart" image apparatuses mean for painting? Redundancy or renewed purpose?

Mary Ramsden: It's difficult to not sound nostalgic in this regard but I do think painting is about paying deep or close attention with an intensity we're gradually losing. This isn't just about technology proper, but how technology has affected the speed of things, culturally: apps for meditating on a packed tube, sharing "life hacks" on how to cook a meal in 10 seconds flat, and a myriad of suggestions about how to achieve things without actually doing them with your hands. I use my phone as much as anybody, especially as a reference bank when I'm working but I think there's really something crucial about pace of production and of looking at something handled that can encourage us to slow the fuck down, something essential about what it is to be human.

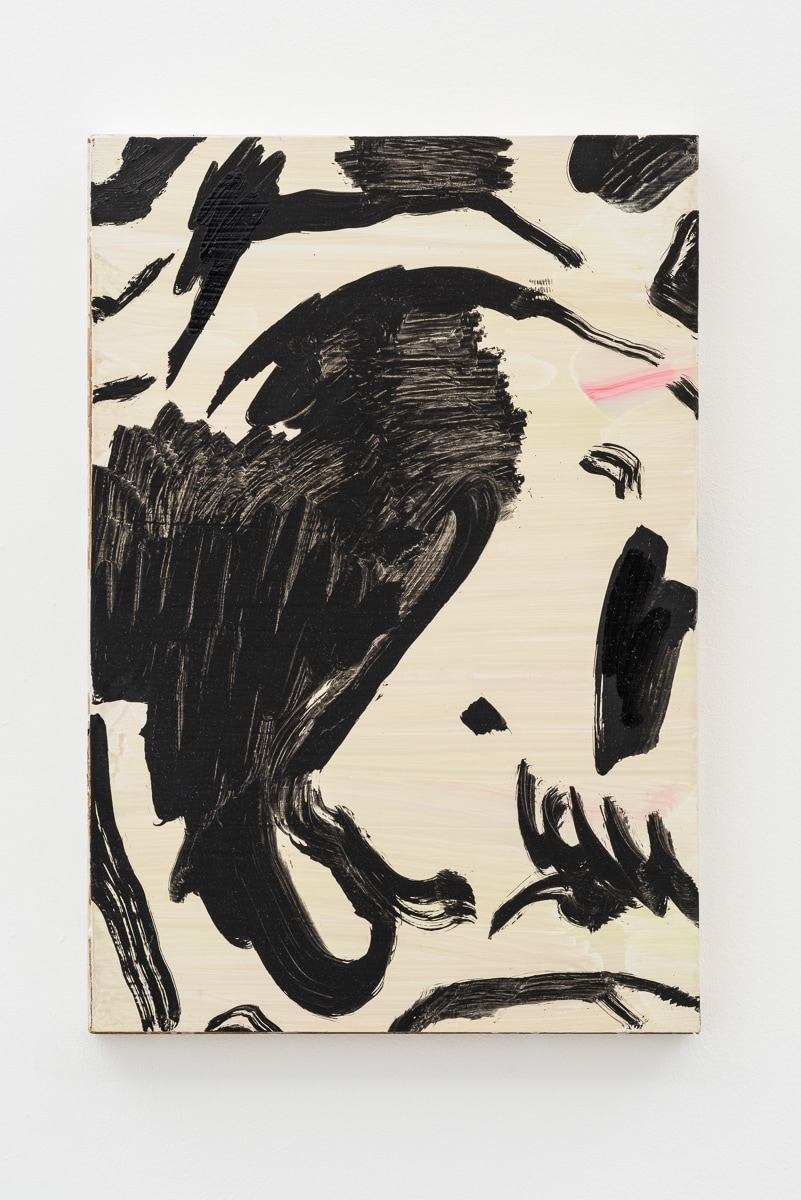

IH: Love hearts reappear often in this series of works, symbols that function in social media and instant-chat applications as hasty shorthand for agreement or a public, conciliatory gesture. Here, they are elongated, distorted, and roughed about. Can you speak a little about your choice and treatment of this symbol?

MR: I decided to use that "like" ideograph as a familiar and recognisable entry point into the work that bridges a gap between a digital space and a painterly one. I was curious to handle that ubiquitous graphic and push it around with a freehand approach as a way to investigate the different speeds of those two things side by side. I'm less interested in the use-value of the specific button [the heart emoticon] than the world it inhabits.

IH: Base colour is really important in these works, as in previous works of yours. Is the palette for this show conscious or is the combination of mildly toxic pastels and deep, black impasto more intuitive?

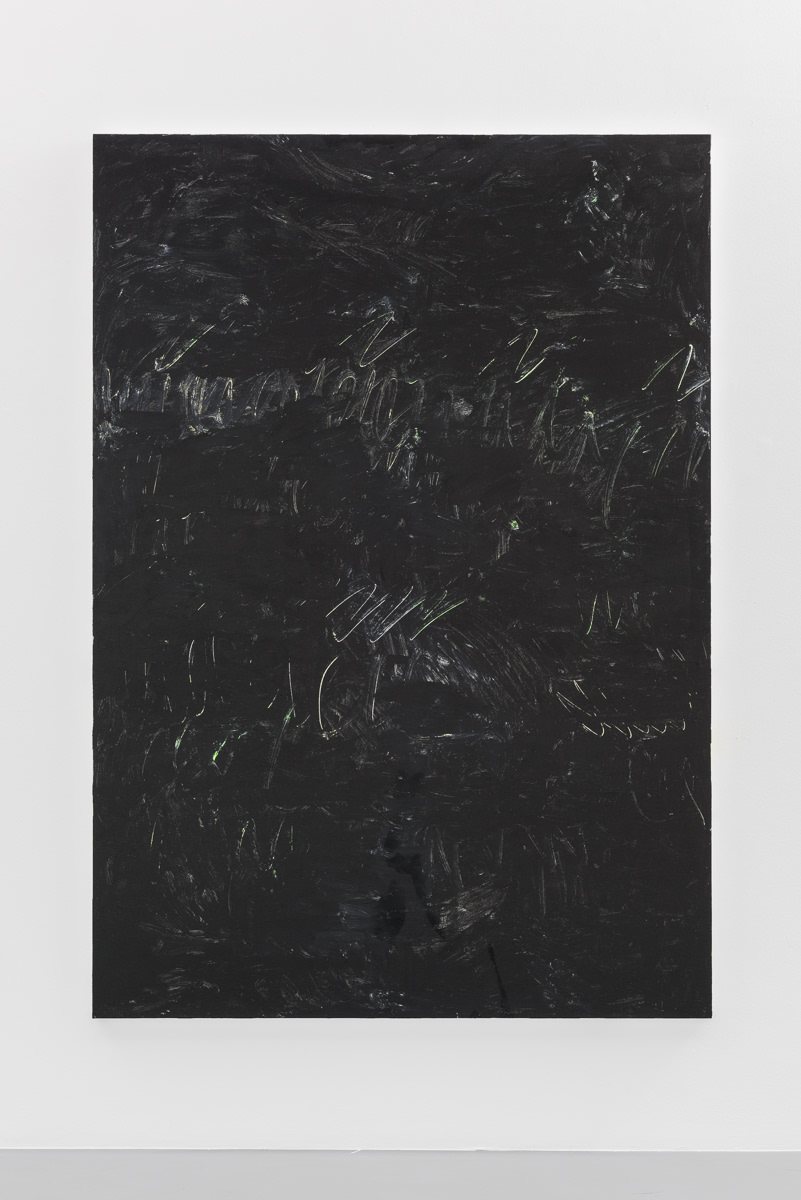

MR: I often work with groups of paintings in clusters that together form one work. The tones of the individual elements are often informed by what's happening in the largest work in a group because it underpins the whole. The different temperatures of each painting are often directed by the base colour so the toxicity or gaudiness might throw off a gentler component, like a particular word that reboots a sentence. It's important that the individual personalities vibrate in unexpected ways and colour is central to that back and forth. I use black in the paintings and Dibond works as a device that speaks about a very particular "splendidly macho" mid-20th century attitude to painting and the use of black at that time in particular, but also about the screen today.

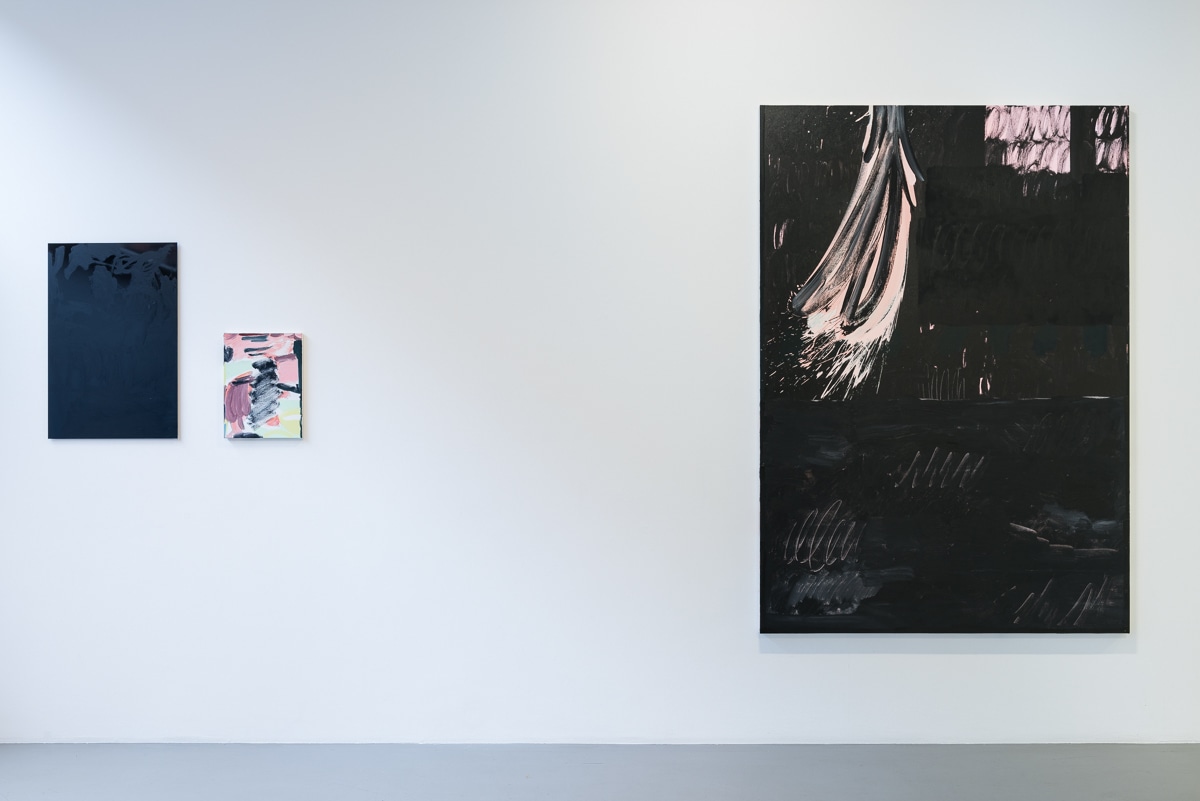

IH: The title of your show is 'Couples Therapy'. Some works function as diptychs, very similar in scale and complimentary to one another (as in 'Naked Scenes', 2017), other duos are antagonist and differ in scale and tempo ('Coping Mechanism', 2017), others fare better alone (the more self-contained 'French Window', 2017). How interested were you in depicting real life relations and human social dynamics in these works? Could we interpret them as a kind of writing through combinations of paintings?

MR: Yes the title of the show is a way to point to a wider understanding of visual relationships that have their own character and points of difference. The viewer plays a vital role in these moving parts and becomes an integral aspect of the group as therapist, or third person in their company, assessing the compatibilities and discordance between the works. I wanted to use a title that stepped away from painting but was a nod to those intentions.

IH: You have asked two writers to contribute short prose pieces in response to the paintings. Can you explain what compelled you do so and what you think this brings to the exhibition?

MR: I invited two writers to work on separate short stories that relate back to the show title. I have worked with writers Adam Thirlwell and Leanne Shapton for the past two exhibitions and I wanted to continue this relationship between image and text as writing has a strong influence on my practice so asked Aria Beth Sloss and Mave Fellowes to collaborate with me on this show. The motifs and marks in the work are sort of stand-ins for language, both in the works and their original function in the world. I wanted to bring the show back to the source but outside of the image in a collaborative way.

IH: There are a number of paintings that I think of when I look at these works-including Roy Lichtenstein's 'Brushstroke', 1965; Jim Dine's 'Four Hearts', 1969; a range of works by Cy Twombly, including 'Bachus', 2006-08; and Laura Owen's 'Pavement Karaoke' series, 2012. How conscious are you of genealogies of painting in your own work, or do you make a concerted effort to disengage from formal lineages?

MR: These artists, among many, are always there in the studio so it's a tussle between very deliberate references to the histories of painting, and the signature gestures within that, but also being acutely aware of what's left. I look to see how that can be messed about with to create something that speaks both about what came before and how those specifics appear to us now, in relation to contemporary culture and painting today. For example the aforementioned New York School utilised black to investigate numerous areas that included both a spiritual inquiry as well as the use of colour (or non-colour) as a means of self-portrait. Understanding these motivations in relation to the black screen of a tablet, as both a reflective surface and the device with which to take a selfie or curate our different selves, is a funny and important juxtaposition to navigate through painting.

IH: Are there artists working in other media with whom you feel a particular affinity, young or old?

MR: I feel that writing is the go-to media for something outside of painting that helps me understand how I want the work to behave. This can be as removed as a poem written in a language I don't speak. It's as much about the sounds within the sentence structure and the form the words can take as it is about content. I find short stories particularly generative as the economy within that form helps me to be rigorous about what is necessary in my work. It makes me brave.

IH: Do you start out with a preconceived idea of how a painting might look at the end of any day, or do these compositions come together over time and surprise?

MR: I have a load of notes that I usually make at the end of each day in preparation for the next with instructions and diagrams and I almost never look at them when I turn up in the morning. I think it's useful to make sense of what went on and then ignore it. I normally have a plan that takes a different turn and if I feel too rigid about what I want it to do then things usually fall apart or feel too restricted and stale, a bit like working for someone else. If I've made a painting that's really working for me and then try to handle the next in the same way it just looks like a bad impression of the last and almost never has the same attitude or assertiveness which is annoying but also helps me trust the value of the thing when it's surprising me.

IH: How important is it for you to explore different material supports on which to paint?

MR: This is a key part of it all and again about the tempo of each thing. Sometimes a group needs a clunky addition, or a slick one or a shallow, slippery support. Other times I'll use a cheap white canvas to bring some informality to the party. It just depends on what's going on about it. I like that it makes the relationships stop or start as you take in works around the room. And sometimes in the Dibond works that "taking in" is reflected back at you.

IH: The works have a great tonal diversity-some seem funny and upbeat, others more somber and insular. How much of your own humour inflects these works, or does their personality appear after the making?

MR: Making paintings can be pretty weird in itself as a sort of performance, particularly with these large works as I can spend half the day hovering over a canvas lying on the floor, rehearsing the move my arm needs to make in order to execute a one-shot mark. I wanted that "painterly" thing, which can be both really serious and a nonsensical, to be visible in the excess flick of paint that comes off these fast gestures. These deliberate paint sprays are pretty funny and comically sexual, less or more depending on how thin I make the paint. I also find that sometimes the almost gross use of colour combinations (that on their own are pastel and gorgeous) can verge on lurid, sickly sweet as in the work 'Hurt Colours', 2017. So if there's a humour in garish colours and a room full of misshapen hearts then great.