Overview

Where the Future Grows is on view at Savile Row.

Memory Lines is on view at Conduit Street.

Read a Foreward by Grant Tyler and essay Freedom and Nature (in the Year 2024) by Dieter Roelstraete, published on the occasion of the concurrent exhibitions.

Pilar Corrias is pleased to present two concurrent exhibitions by Peppi Bottrop, on view across both gallery spaces. In Where the Future Grows, on view at Savile Row, Bottrop debuts a new body of work made on copper mesh, while Memory Lines, on view at Conduit Street, presents a series of monochrome charcoal and graphite works on canvas, alongside Bernd and Hilla Becher’s Blast Furnaces, 1970-94, a typology comprising nine silver gelatin prints.

Where the Future Grows is on view at Savile Row.

Memory Lines is on view at Conduit Street.

Read a Foreward by Grant Tyler and essay Freedom and Nature (in the Year 2024) by Dieter Roelstraete, published on the occasion of the concurrent exhibitions.

Pilar Corrias is pleased to present two concurrent exhibitions by Peppi Bottrop, on view across both gallery spaces. In Where the Future Grows, on view at Savile Row, Bottrop debuts a new body of work made on copper mesh, while Memory Lines, on view at Conduit Street, presents a series of monochrome charcoal and graphite works on canvas, alongside Bernd and Hilla Becher's Blast Furnaces, 1970-94, a typology comprising nine silver gelatin prints.

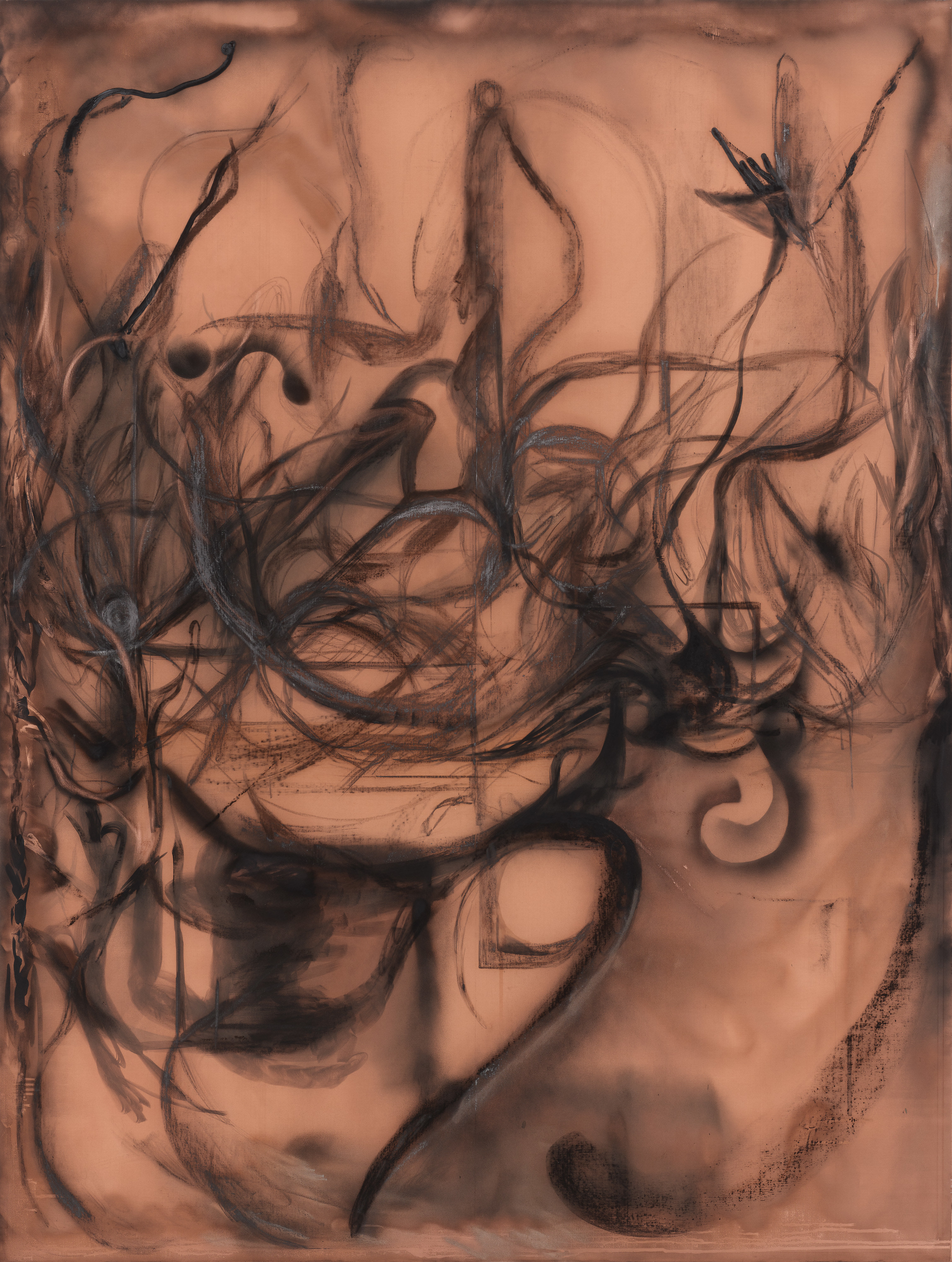

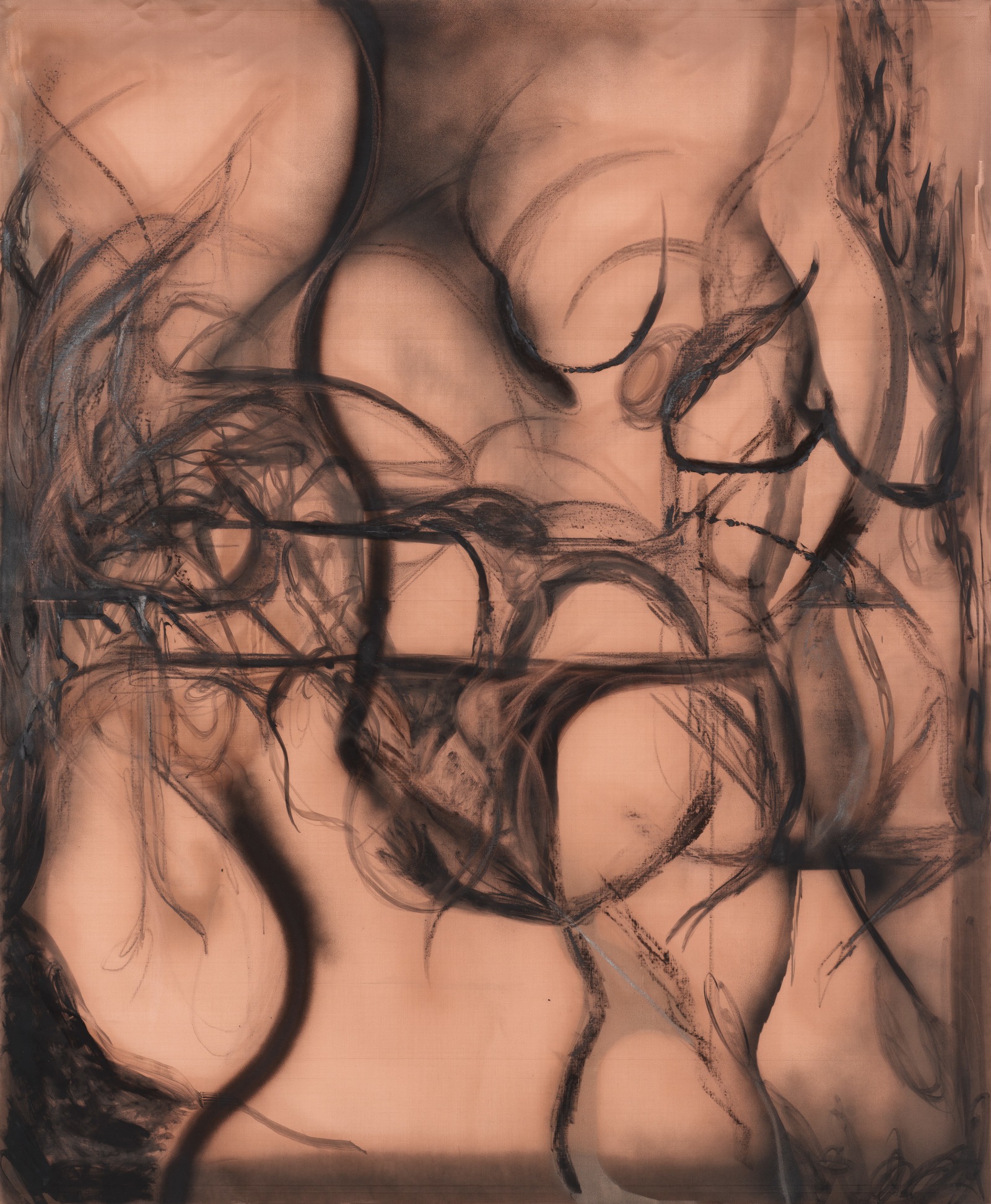

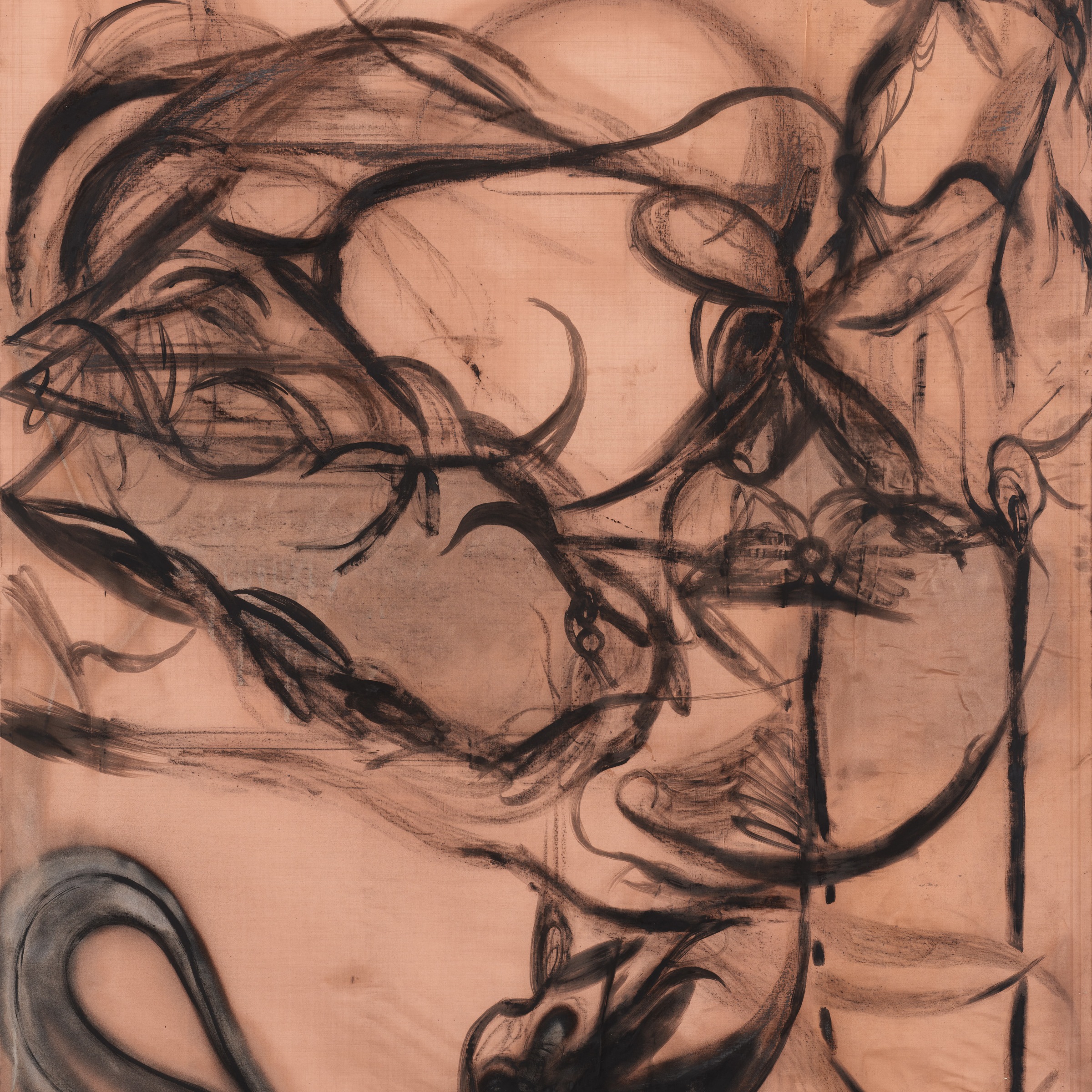

In Bottrop’s paintings, a certain coded organisation along art-historical principles of line, surface and space is linked to the political historicity of his chosen material. Charcoal, copper, graphite and rust are materials with which the artist, as a miner’s son, has always been familiar. Bottrop’s birthplace, the Ruhrgebiet in western Germany, until recently formed the nation’s industrial heartland; providing the essential conditions for steel production, it operated as a key engine room for economic expansion and war. Bottrop’s conceptual investigation of his materials, their substrates and historical infrastructures, offers a way to reframe the conditions and effects of contemporary ideological agendas. Within the artist’s smoky compositions, he asks: how does the spirit of an age become form? How does form become spirit?

Where the Future Grows, an immersive display of gesture, movement and line-making at Savile Row, sees Bottrop newly explore the unique materiality of copper mesh. Copper, unlike linen or canvas, does not stretch in the manner of traditional painting supports. Suspended by stretchers over plywood board, the finely woven mesh establishes a concrete spatial relationship with its support – casting secondary marks where black pigment falls through the weave onto the painting’s physical architecture beneath. Scaffold and surface, and the fragmentary images that exist in between, become one.

The artist is attracted to the commonplace material – used as a conductor of heat and electricity, a universal building material, and an essential mineral to all living organisms – for its modesty and ubiquity. In the rhythmic forms of Bottrop’s paintings, the viewer can find echoes of the artist’s body as he toiled with the labourer’s material. However, Bottrop also uses this basic metal to create a charged dialogue between high art and low material, the profane and the sublime, adding a new dimension to the ‘transcendent’ ambitions of traditional abstraction.

In Memory Lines, an exhibition with Bernd (1931–2007) and Hilla Becher (1934–2015) at Conduit Street, fourteen monochrome charcoal works on canvas are displayed in dialogue with the Bechers’ Blast Furnaces (1970–94). The husband and wife duo began their artistic collaboration in 1959 in Düsseldorf and spent the next five decades systematically photographing industrial architecture found across Europe and North America. Their iconic black-and- white images of water towers, gas tanks, blast furnaces, grain elevators and other industrial facades were taken with an effort to remove stylistic intervention – an approach that afforded an examination of the vocabulary of form. In this group of Blast Furnaces, we see the Bechers examining these municipal structures the way a biologist might look at specimens, organising the different examples into species or ‘typologies’.

For Bottrop, whose childhood scenes closely resembled the Bechers’ visual landscapes, their vocabulary of forms share a dialect: they are sites, beyond time, where raw material and labour are extracted and transmuted, literally and symbolically. In charcoal and graphite on canvas, Bottrop responds to the Bechers’ typology with organic forms that draw up from the earth into the sky like plants. Despite their monumentality, the austere forms of the blast furnaces have mostly since vanished from the Ruhrgebiet. Bottrop’s new works share with the Bechers’ typology a memory of the past and a devotion to the austere beauty of simple, industrial forms and materials.