Interview with Sedrick Chisom

Pilar Corrias: Could you talk us through the process of making a painting? From the initial concept to finalising the work.

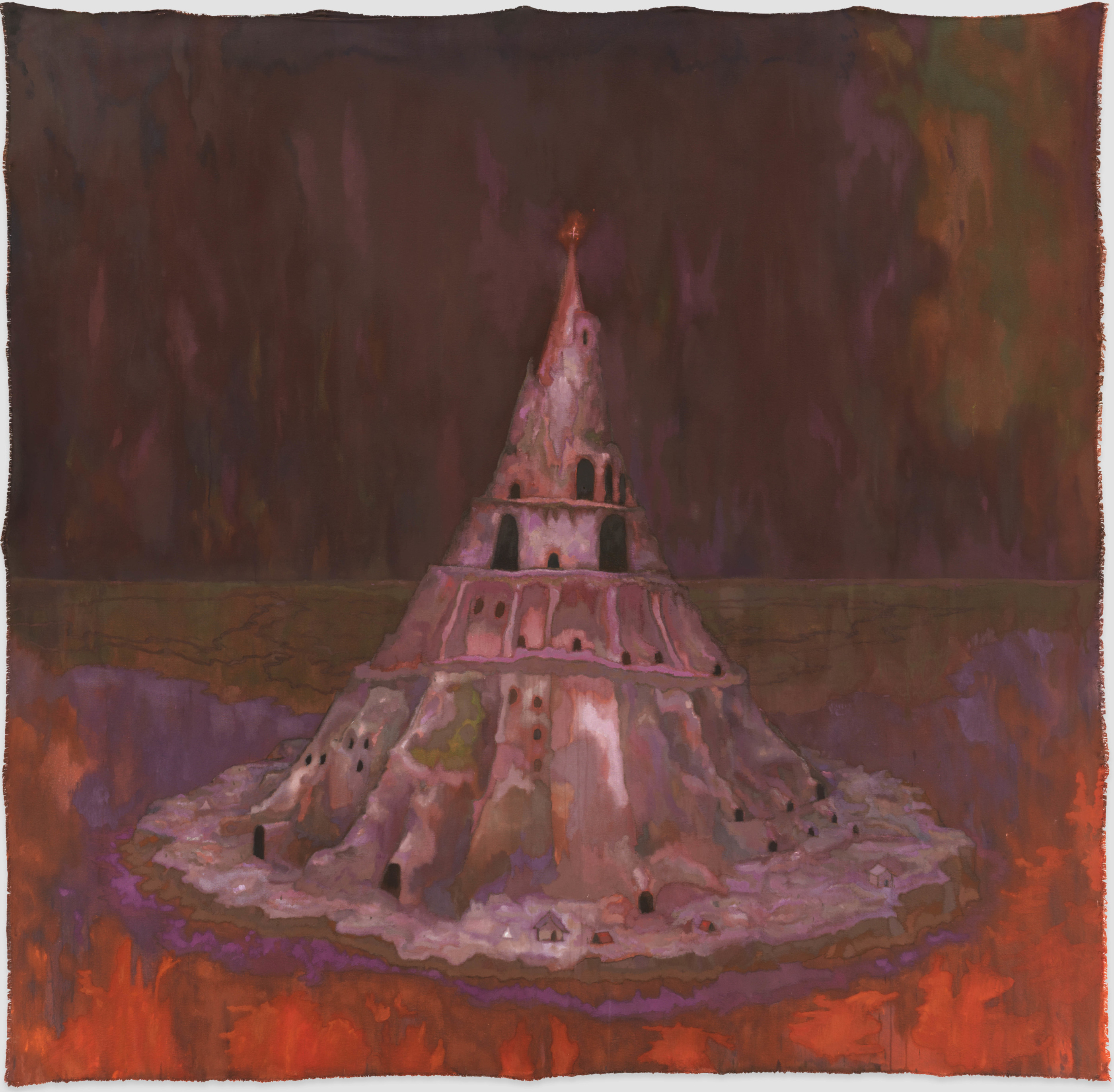

Sedrick Chisom: Every single painting and drawing I've made since 2018 has been part of one singular dream narrative series. My process itself is quite fluid and couched in a lot of experimentation, so whatever I describe will be too neat and misrepresent what actually goes on. Mainly, I just draw and paint a whole lot and read a whole lot. My studio is always like a chaotic playground… I usually start the paintings by building up a surface to the point that it becomes very active to allow for some discovery involving how to respond to the surfaces later on. The paintings begin as abstract color-field atmospheres. I then start looking into the atmospheres trying to make out and imagine specific forms in the incidental shapes that were produced, and trying to imagine a scene from the world of my series of paintings that suggests itself in these firms. I then go through a box of printed out references (film stills, victorian illustration, Goya's prints, civil war photography, medieval christian painting, imagery from black culture, postcards, etc…) choosing based on my imagined scene, and I will make drawings of the print references, combining them all into a single line drawing. It's important that I maintain some distance from the prints since the paintings are not intended as acts of mediating photography or any other media other than my own drawings. The process of drawing works to transform the initial reference via the use of stylised undulating lines. From this point, I will either paint from the small drawings directly or use an old fashioned photo enlarger to project the drawings to the surface. Planning makes me uneasy and I have an instinctual urge for spontaneity so I use water soluble dry media to do underdrawing since the material will quickly dissolve or blend with the paint when I lay down a mark in acrylic. At this point I'm exploring colour and light scenarios and scraping, and spraying, and smearing, additively with thick or thinned down paints. I usually paint on paper but back the paintings on paper with raw canvas. Paint would often drip to the other side and bleed into the canvas. This discovery encouraged me to explore painting on raw canvas with thin paint.

PC: During the walkthrough of your most recent show at the gallery, Condo 2020: Westward Shrinking Hours you brought up a three act play you wrote for your thesis, and explained how the play and the works shared the same context (same world, same timeline). Could you tell us more about the play and its relationship with your work?

SC: The language of the titles deeply informed my approach to writing the play. The idea of even writing the play actually grew out of the titling process. People sometimes ask me if the paintings are illustrations of the play, sort of like how painting used to illustrate the bible. Actually the relationship between imaging and writing is destabilised such that I would look to the paintings to figure out what to write about and to the titles to figure out how to even write in the first place. Actually, looking at 30 paintings or so, I see them sort of like denominations within a decentralised church such that they both share the same exact mythology, characters, and dream narrative context but the two media differ on their opinions of what is of canonical importance, sort of like how the Virgin Mary occupies different positions within the Christian pantheon depending on the denomination. Where the play and the paintings share themes of toxicity, mutation, nuclear destruction, climate-change, the second coming and the collapse of evangelical white nationalism they differ in that the play is much more concerned with narratives of purity and its subtext of ethnic cleansing or even genocide. The play follows a discrete group of Confederate/Union soldiers and a certain Angel of The Lord from Mormon mythology who neurotically obsess over the colour of their phlegm as a portent to the state of their bile. The outcome of the play's narrative essentially sets up the desperate conditions of the protagonists in many of my paintings who wander unstable wastelands that fluctuate between hot and cold in isolation.

PC: Can you talk us through the process of titling your paintings?

SC: Like I said, the language of the titles actually deeply informed my approach to writing the play and sort of grew out of the titling process. After I wrote the play, the situation changed so that the play gave me a great deal of language to use as material for titling the paintings. Initially titling was very intuitive, now it's much harder and takes a lot longer to arrive at a title. Not so much because I'm struggling to find words but because I'm being careful of maintaining continuity within the series. Titling for me is a way of maintaining a certain order within the paintings and establishing relationships between paintings via invoking the repetition of key words from earlier works.

PC: Could you tell us more about the use of colour in your work? The iridescent pinks and bright greens seem to resonate with the polluted, toxic world in which these figures find themselves.

SC: The colours are used to conjure associations with toxicity, hallucinatory wastelands and heat vision technology. For a while the colours in the paintings would fluctuate quite wildly from painting to painting. To me this implied a world that was fluctuating violently from hot to cold, and from night to day. And then last year the colours in my work began to converge towards a very cold nighty palette that used greys, whites, blacks, dark greens, and midnight violets. The scenes in these paintings were more quiet, haunted, and creepy, and described some sort of bodily transformation occurring. For my show in London, I wanted to have a dramatic shift in colour. I wanted the scenes to exist sort of at a peak warmth to convey the sense of a manic heady world like the experience of a heat stroke. To me it was as though something had erupted, or the scenes in the painting were during a solar flare. Right after, I returned to this palette but decided to cool it down and shift towards midday and night, imagining that the worlds were like a red dwarf rapidly burning through energy and cooling down.

PC: What are the main sources of inspiration in your practice?

SC: I have a vast collection of visual references that I turn to. Specifically, I draw from Golden Age British illustrators who pictured otherness and orientalism and ethnography such as Edmund Dulac, Arthur Rackham. I look to these illustrators heavily in order to exam how they pictured notions of "elsewhere". Goya's "Los Caprichos" series of etchings gives me so many ideas about how to set up a scenario with only a couple of characters. Mainly, I look at Gauguin and Rothko for color and light ideas these days. Artists who inspire me to go to the studio when I look at their work are Marlene Dumas, Hurvin Anderson, hildur ásgeirsdóttir jónsson, Lisa Yuskavage, Per Kirkeby, and Kathy Bradford. In terms of texts, the work is informed by "The Turner Diaries" (essentially the white nationalist bible), Nell Irvin Painter's "The History of White People", Tony Morrison's "Playing in the Dark", John Block Friedman's "The monstrous races in Medieval art and thought", and Priscilla Wild's "Contagious: Cultures, Carrier and the Outbreak Narrative."

PC: What are you working on at the moment?

SC: Right now I'm in the process of making a lot of line drawings from my collections of photographs. The drawings will likely find their way into being realised as future paintings or charcoal drawings at some point.